Spread and Pass, Brian Kelly’s (Somewhat) New Irish Offense

While the defense may be a bigger problem, one of the primary concerns for many Irish fans is the spread passing offense of new head coach Brian Kelly. Kelly makes no secret of his offensive goal, he wants to be aggressive and vertical, scoring on every possession. As such, he favors the pass over the run, operates heavily from the shotgun, and employs an up-tempo pace.

Some question the lack of a consistent, power running element while others worry about ball control. There are also concerns about the how a spread passing scheme will fare against good defensive competition and Kelly’s ability to fill the roster with elite talent at the skill positions.

Former head coach Charlie Weis’ recruiting record should be enough evidence to negate the last of these concerns, but the others may be valid. There are certainly negatives that come with Kelly’s offense, but many successful teams like Utah, Boise State, Texas, Oklahoma and Florida run versions of the spread, and excel doing it.

So what is a spread offense and how does Kelly’s particular brand work? Furthermore, what is the fundamental problem with his approach and is it compatible at Notre Dame?

What Is Kelly’s Spread Offense and How Does It Work?

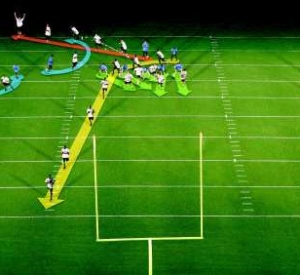

At a fundamental level, the intent of a spread offense is to stretch the field horizontally with multiple wide receivers. This effectively accomplishes two goals. First, it makes crisp tackling in open space a valued commodity. And second, it forces defensive coordinators to use smaller, quicker personnel, and to empty the box in order to matchup on the outside. The result is an advantage for the offense on the interior. Defenses can’t overload the box and the offense has one-on-one blocking opportunities in the running game and in pass protection.

The guys over at NDNation asked Chris Brown of Smart Football to summarize Kelly’s flavor of the spread. True to form, Chris penned a solid synopsis. He makes some excellent points and the entire read is worth the time, but a few highlights are noted here with some additions of my own below.

- Kelly’s offense is a “traditional” spread that, for the most part, maintains balance and doesn’t tilt too much towards the run (e.g. Michigan) or pass (e.g. Texas Tech).

- The run game is simple, particularly without a running quarterback. There is a lot of zone blocking and Kelly’s approach is based on space and angles rather than power, but he does make frequent use of a lead blocker. Mostly, he utilizes inside and outside zone running plays, counters, and some power runs.

- The concepts in the passing game are almost equally simple. Kelly prefers a vertical stem route tree aimed at getting upfield while giving the same initial post-snap motion. This accomplishes his goal of being aggressive, but also detracts from the ability of opposing defenses to read routes as they all appear similar through the first several steps.

- Kelly also likes to use overloaded formations to isolate receivers on the backside. This generates favorable one-on-one matchups for players like wide receiver Michael Floyd or tight end Kyle Rudolph, or overloads the strongside of the field if the defense rolls the coverage to double the weakside receiver.

Some Additional Discussion Points…

Brown states that Kelly’s offense doesn’t make use of the fullback or tight end as much as Oklahoma or Texas, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t use them at all. His running game often employs playside down-blocking and pulling linemen, tight ends, and/or H-backs that lead into the hole (counter and power plays). This is somewhat similar to the traditional counter-trey, albeit with much different personnel and run from spread formations.

Unlike Weis’ offense, in the future Irish signal callers won’t be tasked with an extremely high burden of execution. In Kelly’s scheme the quarterback position is primarily one of distribution. The offense uses similar concepts to combat the blitz, e.g. hot routes and sight adjustments, but the implementation is simple and requires less precision. Moreover, most of the drops in Kelly’s offense are fairly short and facilitate a quick release.

This simplicity translates into a high level of execution. Kelly’s offense is explosive, but the goal isn’t always to go downfield. He wants to accomplish what spread concepts were invented to do (stretch the field horizontally, empty the box and generate good one-on-one blocking opportunities, force open field tackling, etc.), but he mostly does this using complementing looks and concepts, rather than trying to intentionally generate a big play. Additionally, he wants to put a lot of pressure on opposing defenses by operating at a high pace, getting as many snaps as possible, and wearing defenders down.

In this regard, there should more consistency than the Irish offense displayed the past three seasons. Weis relied heavily on the big play, both as a form of randomness and as a catalyst for production. And, as Brown notes, this is why his offense required elite, experienced talent to effectively operate, and why it would be explosive at times and practically dormant at others.

What’s the Fundamental Problem?

In Brown’s opinion, the biggest question mark is if the offense can win the matchups generated by spreading the field.

Talented teams like Oklahoma, Texas and Florida use a spread scheme because they can recruit an abundance of skill talent. They want to get as much of it as possible on the field, isolate defenders, and win the one-on-one battles. Few teams have two good corners, let alone the four or five needed to effectively matchup against a spread offense with good wide receiver depth.

But this comes with the assumption that there is a threat to run and that offensive line can protect the passer, often times with little or no help. As recent Irish fans can attest, this isn’t always the case.

Last year the Irish had plenty of skill talent capable of winning one-on-one matchups (Floyd, Rudolph and wide receiver Golden Tate to name a few), but the offense frequently stalled due to the inability to keep opponents off-balance with the run and protect the quarterback with five and six players.

In other words, spread offenses are controlled by defenses that are able to contain the run and get pressure with four, drop seven, and play physical, press coverage on the outside.

The pressure from the front four allows the defense to drop multiple defenders and minimize passing lanes. The press play on the outside disrupts route running, frustrates timing between the quarterback and his receivers, and forces the passer to hold onto the ball. And the combination of the two allows aggressive outside secondary play with help over the top to prevent downfield throws.

If the offensive line can’t provide extra time for the quarterback, the passing game struggles. Alternatively, without a solid run presence to take advantage of the even numbers in the box, the defense isn’t required to adjust, commit more defenders to stopping the run, and open up the outside.

For most defenses, this is not an easy proposition.

But against USC the Trojan front four dominated the trenches, and the Irish struggled. Quarterback Jimmy Clausen was frequently pressured and the Irish had a razor-thin margin for error. The offense was productive at times, but largely inconsistent.

Likewise, Kelly’s offense was dismantled in the Sugar Bowl against Florida. Quarterback Tony Pike rarely had time to throw as the Gator defensive line consistently applied pressure. The corners played aggressive, tight coverage on the outside, and, without solid rushing production, the linebackers were able to flex and run free. There was obviously a huge talent gap at work as well, but (at least for the Bearcat offense) it was most evident in the line play.

Will It Work at Notre Dame?

There’s really no way to know.

Kelly’s offense has been successful everywhere he’s been and provided he recruits well he will have more talent at Notre Dame than any of his previous stops. This should help with the athleticism mismatches evident in the Sugar Bowl.

Additionally, Kelly’s approach differs from Weis’ style in that there is more focus on the running game, it is based on simplicity and execution rather than complexity and scheme, places less execution burden on the quarterback, and is less deliberate and predictable. All these things will certainly help.

But it still comes down to having balance and being able to protect with five—this is the crux of the problem.

The running game must be serviceable enough to force defenders into the box and prevent opposing defenses from keying on the pass and rushing the quarterback without restraint.

And the offensive line must be able to take advantage of the equal numbers in the box by winning the one-on-one battles. If opposing defenses are able to stop the run and consistently generate pressure with four or five defenders, Kelly’s unit will appear eerily similar to Weis’ squads of the past few years.